By Christian Morgner, Senior Lecturer, Sheffield University Management School, United Kingdom

Addressing the risk of heatwaves appears to be a very objective risk, as the rise in temperatures can be measured, and it is known that sudden spikes in temperatures or prolonged periods of heatwaves increase the risk of death. Owing to the basic physical characteristics of human beings, this seems to be relevant for all of humanity. However, while it appears to be a common risk, considerable research indicates that the perception of this risk varies greatly not only across the globe but also within South-East Asia. One of the key factors to explain such variations is to consider them from the perspective of the Cultural Theory of Risk as developed by Mary Douglas and Aron Wildavsky (1983, see also Thompson et al. 1990). Their approach suggests that avoiding deaths from heatwaves requires not simply considering solutions in terms of physical infrastructure, for instance, access to shelter or water, but understanding how and under what circumstances heatwaves are perceived as a risk, so that people take action or not. This is important for policymakers, because not taking this cultural dimension of risks into account ignores the understandings and needs of people who share these views (Dake 1991). A risk strategy needs to be co-developed with them based on their cultural perceptions of risks.

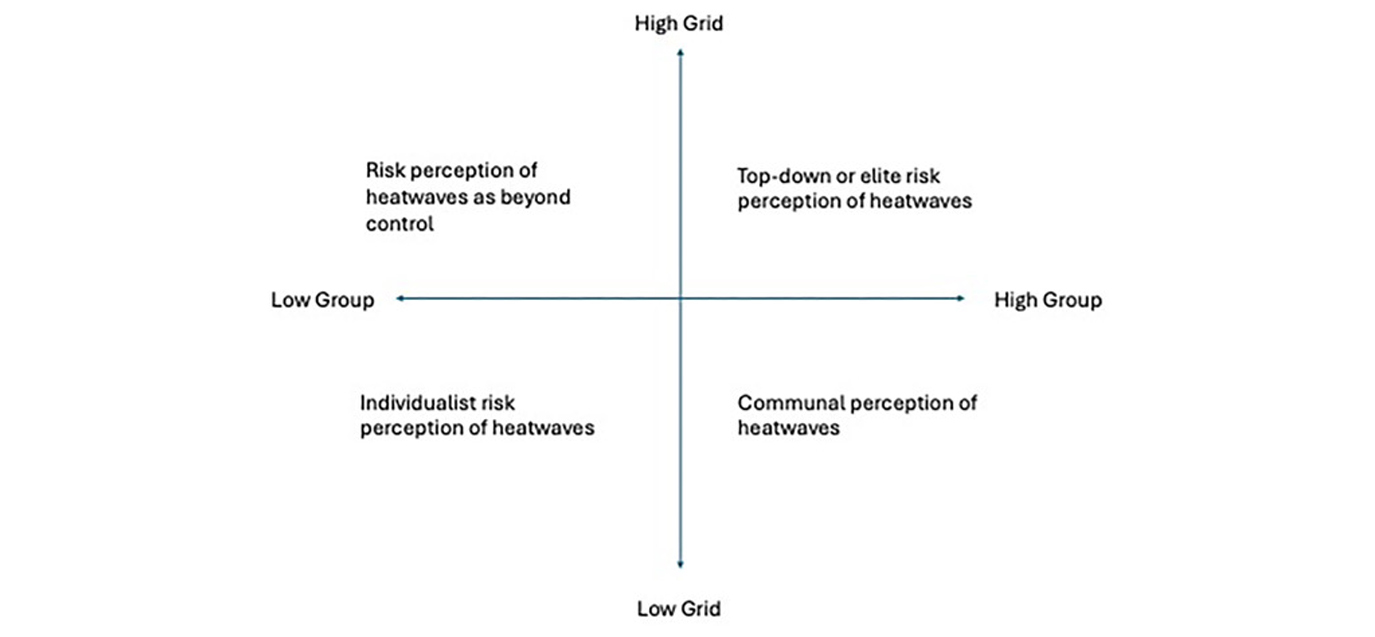

The Cultural Theory of Risk introduces the concepts of “group” and “grid” to describe the competing structures of social organisation. The group dimension refers to the extent of collective control within a society. A “high group” society exhibits strong collective control and communal responsibilities, whereas a “low group” society emphasises individual autonomy and self-sufficiency. The grid dimension pertains to the degree of stratification within a society. A “high grid” society is characterised by conspicuous, durable hierarchies and role differentiation, while a “low grid” society features more egalitarian social relations. Based on these different cultural values, Cultural Theory as developed by Douglas and Wildavsky posits that the group-grid dimensions give rise to distinct ways of life, each associated with specific risk perceptions. These ways of life include egalitarian, collectivist societies (“low grid”, “high group”) that are more inclined to perceive environmental disasters as significant threats, justifying the need for restrictions on behaviours that produce inequality. In contrast, individualistic (“low group”) and hierarchical (“high grid”) societies are more likely to downplay environmental risks to prevent interference with established social orders and protect commercial and governmental elites.

In Southeast Asia, societies with a “high group” orientation (Karen People of Thailand and Myanmar; the Minangkabau of West Sumatra or Toraja of Sulawesi), where community bonds and collective responsibilities are strongly emphasised, may perceive the risk of heatwaves as a collective challenge that requires communal action. In these communities, heatwaves are seen not only as a physical threat but also as a social one, potentially disrupting the harmony and well-being of the community (see Mercer et al. 2008). To address this cultural need, a more collective response to heatwaves is required, for instance, some societies in South-East Asia have adopted the concept of cooling centres as a formalised public health response to heatwaves. These actions reinforce the societal structure by promoting cohesion and mutual aid in the face of environmental threats.

Cities like Singapore, Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia), Bangkok (Thailand), and Jakarta (Indonesia) exhibit characteristics of “low group” societies due to their urbanisation and cosmopolitan nature, approaching the risk of heatwaves differently. Individuals in these societies prioritise personal adaptation strategies, such as the use of air conditioning or personal cooling devices, reflecting a more individualistic approach to risk management (Norgaard 2006; Luber & McGeehin 2008). This response aligns with the Cultural Theory’s suggestion that individualistic societies are more likely to downplay collective risks in favour of personal freedom and autonomy.

The “grid” dimension further complicates the perception and management of heatwave risks in South-East Asia. The royal and aristocratic traditions in Thailand, the ethnic stratification in Malaysia (Bumiputera policy), or certain regions in the Philippines exhibit “high grid” characteristics, where social roles and hierarchies are well-defined and rigid. The response to heatwaves might be structured around the existing power dynamics. Authorities in such societies typically implement top-down measures to manage heatwave risks, such as issuing heat alerts or mandating work stoppage during extreme temperatures (Bankoff 2003). These measures reflect and reinforce the stratified nature of the society, where adherence to roles and respect for authority are paramount.

In contrast, some indigenous and tribal communities in Southeast Asia demonstrate “low grid” characteristics, for instance, the Semai people of Peninsular Malaysia, but also social movements and advocacy groups are characterised by more egalitarian social structures, fostering a more participatory approach to managing heatwave risks (Ebi & Semenza 2008). Community-led initiatives, collaborative planning, and shared decision-making processes may prevail, reflecting a collective belief in the equal distribution of responsibility and authority. For instance, in Malaysia, local communities are involved in ‘gotong-royong’ activities, a traditional communal work practice, to clean up and maintain local rivers and lakes that contribute to cooling the environment. This approach not only addresses the immediate risk posed by heatwaves but also reinforces the societal value placed on egalitarianism and collective action (see Lefale 2010).

The Cultural Theory of Risk elucidates the complex interplay between societal structures and the perception of environmental threats like heatwaves. In Southeast Asia, this interplay manifests in diverse responses to heatwaves, shaped by the underlying cultural values and social organisation. Understanding these dynamics is crucial for developing effective, culturally sensitive strategies for heatwave mitigation and adaptation in the region. It highlights the importance of tailoring responses to fit the societal context, leveraging communal bonds in “high group” societies, and respecting individual autonomy in “low group” settings, all while navigating the challenges posed by social stratification in “high grid” environments and fostering participatory approaches in “low grid” contexts. By applying the Cultural Theory of Risk, policymakers and communities can better understand and harness the social and cultural dynamics at play in managing the risks associated with heatwaves in Southeast Asia.

References: