By Dr Winifred Ekezie, Co-Director of Centre for Health and Society, Aston University, UK; Evidence Synthesis Coordinator, Avoidable Death Network, UK

Climate change is increasing the frequency, intensity, and duration of heat extremes and directly impacting health in several ways, including leading to deaths and illness, which are often avoidable (GHHIN, n.d). As climate change progresses, related negative health impacts worsen with progressive global temperature warming.

Heatwave is defined in different ways. Generally, people can manage during low-intensity heatwaves, but increased heatwave has severe health implications. Heatwaves amplify many health and economic risks, including increased deaths, drought, wildfire, agricultural losses and reductions in worker productivity. Heat-related deaths start at relatively moderate warm temperatures, with thousands of deaths yearly even without temperatures high enough to trigger a ‘heatwave alert’.

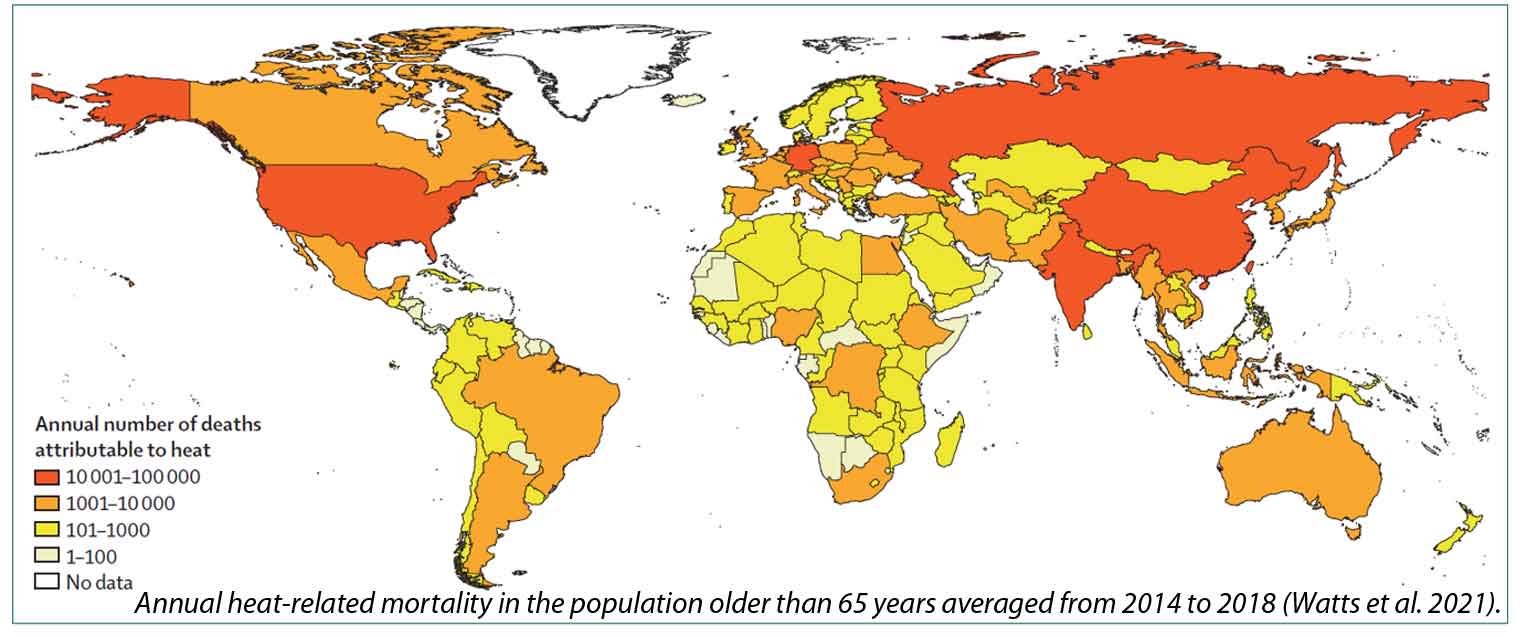

Some populations are more vulnerable than others to an increased risk of death from heat exposure. Age, gender, pre-existing medical conditions and social deprivation are critical factors related to how people experience heat-related health outcomes. Over the past 20 years, heat-related mortality globally in people older than 65 years has reached about 300,000 deaths in 2018, the majority occurring in Japan, eastern China, northern India, and central Europe (Watts et al., 2020).

Consequently, heatwaves are one of the most dangerous natural weather hazards that contribute to avoidable deaths. Population exposure to heatwaves continues to increase with additional temperature warming, and there are strong geographical differences in heat-related mortality, mainly affecting locations with the least resources, interventions and adaptations. Heat outcomes are intensified in urban cities, overpopulated regions, and areas with worsening air pollution and poor key infrastructures for mitigating and managing heat effects (GHHIN, n.d.). About half of the global population and more than 1 billion workers are exposed to high heat and about 30% of exposed workers experience negative health effects. The excess heat-related deaths are avoidable with appropriate heat action plans and strategies (Ebi et al., 2021). However, people still suffer and die unnecessarily due to heat, as population health needs and community vulnerability are often unrecognised.

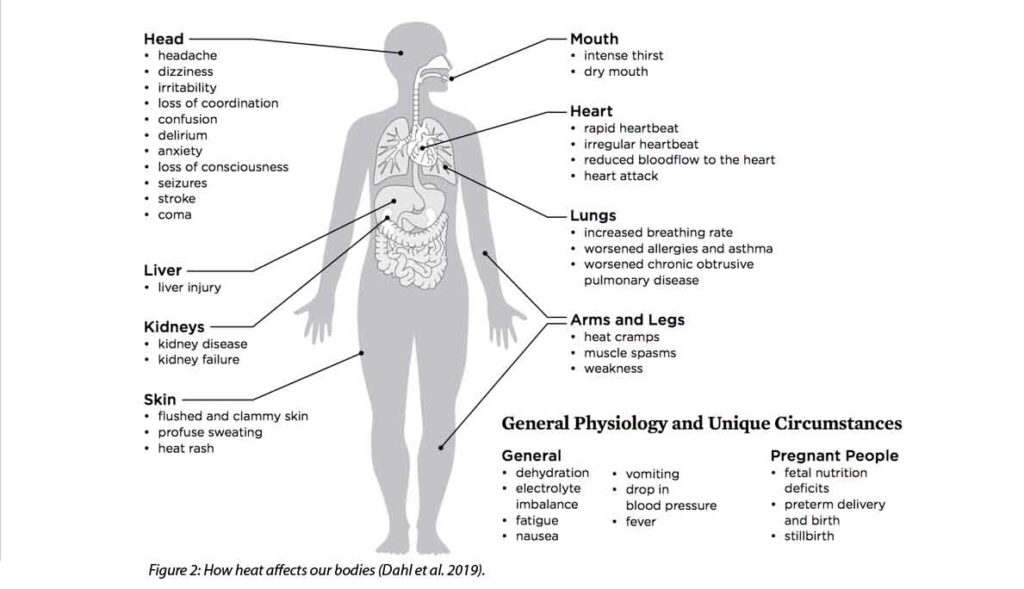

Extended exposure to significantly higher-than-average temperatures compromises the body’s ability to regulate temperature and can result in various illnesses, including heat exhaustion, heatstroke, hyperthermia, and dehydration. Other indirect effects include worsening chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular, respiratory, cerebrovascular, kidney diseases and diabetes-related conditions. An overview of how heat affects different parts of our bodies is shown in Figure 2. Heat health effects also result in deaths and hospitalisations when care is delayed or not provided, but the outcomes can be managed to minimise avoidable deaths.

Heat-related health impacts are projected to increase with climate change without strong adaptation and mitigation efforts, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Ebi et al., 2021). Under a high-warming scenario with no appropriate climate adaptation, there will be hundreds of thousands more heat-related deaths each year in the next few decades. Overall, heat death prevention requires actions at different levels. To minimise heat-related avoidable deaths, there is a need for early identification of who needs to be reached and how best to do so, particularly those most at-risk, like older adults, those with chronic illnesses, and those who work in high-temperature conditions. Therefore, understanding the intensity and impact of heatwaves is crucial to being better prepared and protecting people’s lives.

References:

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this piece are those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of AIDMI.