By Nyima Dorjee Bhotiya, Dipak Basnet, Tek Bahadur Dong, Anuradha Puri, and The Sajag-Nepal Project Team, Nepal

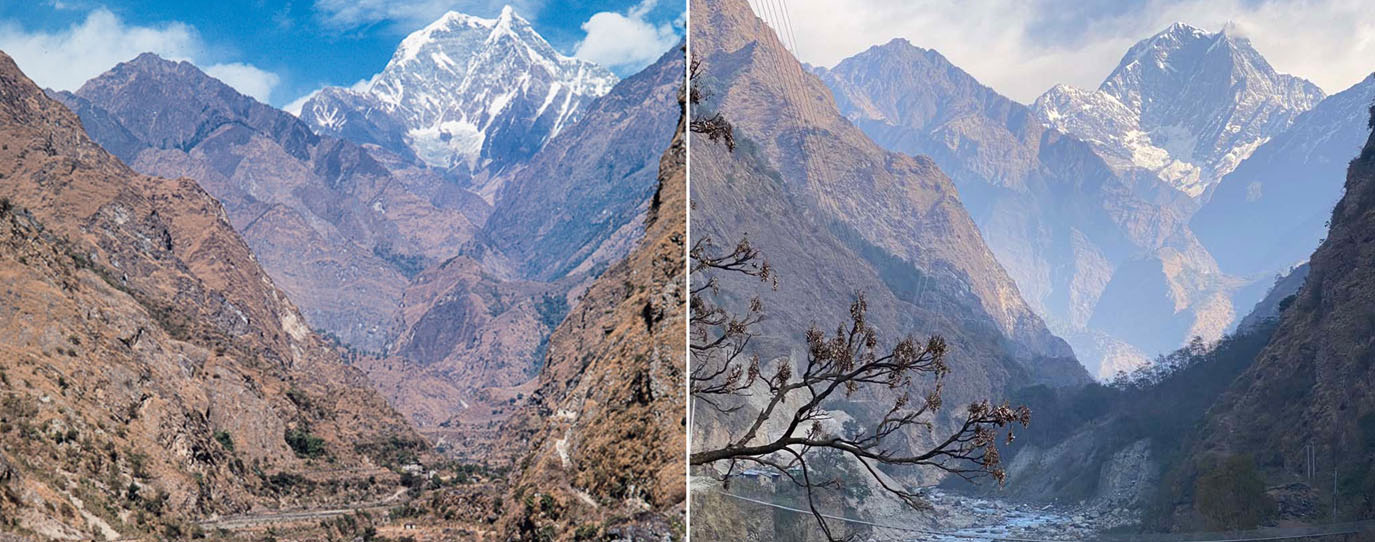

In recent decades, the South Asian nation-state of Nepal has been experiencing increasing and cascading disaster events as vulnerable populations confront a dizzying scenario of earthquakes, monsoon landslides in the middle hills, and flooding along the Himalayan river valleys and the Tarai Plain.[1] Although earthquakes, landslides, and floods are linked with Nepal’s geography, they occur within the larger context of Nepal’s development trajectory and anthropogenic climate change.[2] Communities living in the mountain, hills, and Tarai regions of Nepal for longer periods of time, have developed embodied knowledge and practices to assess and respond to changing hazards in their landscapes and apply their knowledge to reduce disaster risks in their communities. Local ways of knowing and anticipating hazards and risks, however, are not acknowledged within disaster governance frameworks and policies in Nepal. Despite their localisation with promulgation of the federal Constitution of Nepal 2015, these policies remain focused on technocratic intervention and top-down approaches to disaster prevention and preparedness planning.

In this essay, drawing from our ongoing research project, ‘Sajag-Nepal: Planning and preparedness for the mountain hazard and risk chain in Nepal’, we describe local disaster risk reduction practices and forms of knowledge which are place-specific and informed by the local and indigenous community’s knowledge of their landscape and its environment through longitudinal and intergenerational experience.[3] We situate indigenous and local knowledge of hazards alongside the current Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) governance practices to discuss existing gaps of DRR interventions in Nepal and scope for dialogue between local practices and mainstream disaster governance. This essay argues that local ways of knowing the landscape problematises mainstream disaster governance’s efforts at taming the landscape. Bringing the two approaches together in practice and policy can help make DRR more inclusive and diverse.

Taming the landscape: Contemporary disaster risk reduction practice

Hazards such as floods, earthquakes, and landslides are governed at the national and local levels by multiple actors (including bilateral and multilateral donor organisations) and policies using competing paradigms that are often influenced by Western international policies. Despite Nepal’s policies promoting decentralisation in disaster governance as outlined in the Hyogo and Sendai frameworks, practical steps to empower local stakeholders (including the people) and include local knowledge in planning and preparedness are not followed. When it comes to DRR, the central and local authorities tend to prioritise budget, technology, and expertise (engineers and geologists) for intervention and mitigation measures. This approach is influenced by techno-scientific understanding of disaster preparedness and intervention, which privileges a top-down, technocratic approach focusing on engineered solutions to the identification of hazard risks and disaster management process. This is done by taming the hazardous landscape with capital intensive mitigation measures. The practice of building embankments along a river settlement to safeguard against flood risk is a common DRR mitigation in Annapurna Rural Municipality, Myagdi and other river settlements of Nepal. Such mainstream practice of building embankments and other geoengineering solutions to river flooding/cutting attempts to ‘tame’ and control the river without considering its natural capacity. However, such practices often fail and people are caught unaware because they expect these technologies used to control the river to work every time. On this mainstream practice of DRR mitigating measures, drawing from the experience of Thakali, indigenous community with a long history of living in the Kaligandaki river corridor, a young entrepreneur in his mid-twenties explained,

“…riverbed is increasingly being encroached and embankments are being built to safeguard the settlement on a riverbank, however, they fail to anticipate that the river’s nature will revert back to its previous channel which can create a new risk to areas hitherto not considered at risk.”

Furthermore, due to the complex bureaucratic processes, institutional hierarchies, and financial resources that accompany conventional DRR in Nepal, these approaches have proven to be inflexible and ill-adapted to quick changing and cascading hazard contexts. Evidence suggests that reliance on scientific mainstream approaches to disaster management can also have a negative impact on the environment, local community, and even enhance risk.

Knowing the landscape: Local disaster risk reduction practices and knowledge

Parallel to mainstream technocratic conceptualisations and practices of disaster governance are embodied indigenous and local knowledges of hazard and disaster risk. Such knowing of the landscape is diversely practiced and communicated within the communities through non-prescriptive means and conveys ‘where to be’ and ‘where not be’ within the landscape of their knowledge. For example, the saying, “don’t claim ownership of the house on the steep slope or the riverbank” – “भिर र खोला किनारको घरलाई आफ्नो नभन्नुस” (bhir ra khola kinarko ghar lai aafno nabhanus), is frequently heard in our respective field sites, indicating known zones of avoidance for settlement. The community’s knowledge of precarious places to live is rooted in their long history of inhabitation and observance of failing slopes, rockfalls, and flooding. Such understanding of environment and landscape, particularly changing nature of river, is commonly expressed through the proverb, “a river reverts to its old channel every twelve years” – “बाह्र वर्षमा खोला पनि फर्किन्छ” (barha barshama khola pani pharkinchha) which anticipate the changing nature of river channel and risk it poses. This longitudinal experience has allowed them to develop a deep understanding of the landscape and a heightened sensitivity to changes in the environment, particularly in response to natural hazards such as floods and landslides.

Drawing upon this ‘knowing’ of the landscape, the researchers employ various sensory methods to evaluate and respond to anticipated and unanticipated changes which have the potential to lead to disastrous outcomes. In a Kali Gandaki riverbank settlement in Annapurna Rural Municipality of Myagdi, Gandaki province, community members who have experienced flooding multiple times described a sensory method they used to detect a likely flood and need to evacuate to safer shelter. As we explored local practices and knowledge about floods, an elderly man in his fifties shared the community’s practice as follows,

“…during the monsoon months, this river swells with the rainfall, however, we feel the risk of the river to our settlement only when we sense the odor of debris-flow in the river when it carries boulders, gravel, sand and other materials, which cause the change in the river channel and results in erosion of the bank.”

The elderly man shares that a river becomes dangerous only when it carries debris and sediments that can be detected by the smell of the river as it swells during the monsoon months. The statement highlights the community’s knowledge about the river and its risk at certain times of the year that they have adapted with experience and close observation of the river’s nature in different time periods. Hence, they have developed a practice based on their knowledge which helps them to sense changes in the environment and respond to it before risk arises. As such, local ways of knowing the landscape and its environment helps to anticipate disaster risk as well as ‘where to be’ and ‘where to not be’ when the changes are sensed. However, such practices and knowing are not incorporated into the disaster preparedness plan which is primarily a top-down, technocratic, development initiative and Western practice in its orientation and implementation.

To conclude, we urge for the recognition that local knowing of the landscape and mainstream disaster approaches are not inherently contradictory. Rather there is an opportunity for convergence of these two approaches to generate more inclusive and diverse DRR practices at the local levels. In practical terms, we note that climate change and development pressures, such as road and hydropower construction projects are reshaping patterns of migration in the Middle Hills of Nepal. In these circumstances, people can find themselves moving into new environments where their knowledge of hazards and practices of disaster prevention are untested. Sensory knowledge of specific rivers, such as that articulated by riverside communities in Annapurna Rural Municipality’s Kali Gandaki Corridor, is an embodied disaster prevention practice that can be channelled amongst community members without the need of expert interventions, strengthening risk reduction from the bottom-up. Such place-based knowledge can sit alongside and guide technical interventions by highlighting, in this example, the historical course of river movement and recognising the ever-present danger flash floods pose to riverside settlements, regardless of the presence of an embankment or other form of disaster technology. In this way, hazard history, experience, and preventative measures can be taken into the evolving hazard context, creating conversation across indigenous, local, and scientific knowledge communities for the benefit of those most affected by disasters.

[1] Ministry of Home Affairs. Government of Nepal. 2022. ‘Risk to Resilience: Disaster Risk Reduction and Management in Nepal.’ In The Seventh Session of the Global Platform for Disaster Risk Reduction, 23-28 May 2022, Bali, Indonesia. https://dpnet.org.np/uploads/files/Nepal_Position%20Paper_GPDRR2022_Final

%202022-05-26%2016-58-49.pdf ; Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of Nepal. 2017. ‘Nepal Disaster Report 2019.’ Kathmandu: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of Nepal. http://drrportal.gov.np/uploads

/document/1594.pdf

[2] World Bank. 2021. Climate Risk Country Profiles: Nepal. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org

/sites/default/files/2021-05/15720-WB_Nepal%20Country%20Profile-WEB.pdf

[3] Major local and indigenous communities in the four core sites for Sajag-Nepal: Planning and preparedness for the mountain hazard and risk chain in Nepal are Tamang and Newar in Temal Rural Municipality, Kavre; Sherpa and Tamang in Bhotekoshi Rural Municipality, Sindhupalchowk; Magar and Thakali in Annapurna Rural Municipality, Myagdi; and Thangmi and Brahmin/Chhetri in Bhimeshwor Municipality, Dolakha. The local communities refer to the diverse group of community—caste and ethnic groups—who have been living in the hills of Nepal and shares the common ethos and sensibilities of the landscape.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this piece are those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of AIDMI.