By Eleonor Marcussen, Researcher in history, Linnaeus University Centre for Concurrences in Colonial and Postcolonial Studies, Linnaeus University, Sweden

Among historians, it is contentious to say that societies learn from the past. Every change, every occurrence happens in a context. Even if we can replicate an entire scenario from the past, one unexpected butterfly flap or the acceleration of time may affect the constellation and result in a different outcome. Yet, in historical disaster studies, historians concur with disaster management agencies that institutions and societies learn from experiences with disasters in the recent and distant past. Poor building construction or weak institutional infrastructure and not the occurrence of storms or earthquakes per se, are accepted as the root causes of the disastrous effects. Social, political and environmental history address these questions of how social processes shape disasters and populations most at risk. It includes analyses of how technological, political, and cultural factors determine human capacity to deal with hazards, often interlinked with social factors such as gender and age in a complex manner.

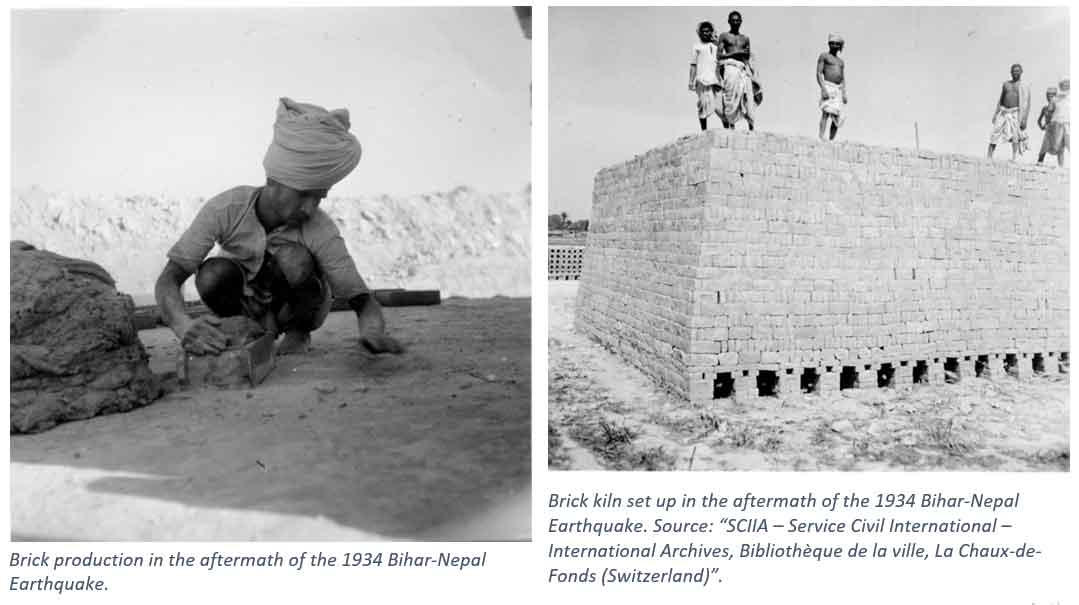

History can, in some ways, serve as a laboratory for comparisons and reflections on how risk is negotiated and persist, rather than being reduced over time. With these reflections, we can argue for the need to pay attention to the importance of placing risk in its social and historical contexts. The 1934 Bihar-Nepal earthquake provides several examples of how disaster management was implemented according to a discourse of modernisation and development. Reconstruction and planning for future earthquake involved experiments with ideas that synthesised knowledge from different fields of expertise. As literature on disasters in the postcolonial era often points out, vulnerability arising from disaster is left out of the development paradigm.

Global Disaster Experts

Turning to global experts in the field of disaster management is not as new as we may think. The rise of experts and professionals affected the field of disaster management already in the 1930s. In 1934, the Japanese earthquake expert Nobuji Nasu (1899-1983) stayed in Bihar for 50 days to research the impact of the earthquake. His work at the Earthquake Research Institute at Tokyo University made him an expert on soil sediments and its impact on surface movements in earthquakes. Bihar, and in particular north Bihar, was already known by then for its dense river systems and recurrent disastrous floods. The changes in land levels and sand deposits in agricultural fields after the 1934 earthquake caused much concern. Nasu held discussions on various impacts with the officers of the Geological Survey of India and commented on seismic damages, based on which he gave recommendations on earthquake-safe buildings.

Japan’s history of earthquakes was essential in forming a global community of earthquake experts, as well as modes for communicating disaster to the public in the inter-war period. The 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake made news for its spectacular destruction and the media coverage it gained was replicated in subsequent earthquake aftermaths. Photography and news reporting helped collect disaster relief from around the globe on an unprecedented scale in its aftermath. These media images of disaster were still fresh in mind in the aftermath of the 1934 earthquake, which would be the first South Asian earthquake extensively documented in photographs in national and international news outlets and that too from the air as well as in walk-through footage of ruined urban landscapes. From the start, aeroplanes accidentally played an important role. A commercial aeroplane had by chance flown over Muzaffarpur on its way to Calcutta (now Kolkata), and in response to the message ‘Earthquake Take Care’ chalked in white across the ground, it had landed among the cracks and fissures at Sikandar maidan. In the immediate aftermath, aeroplanes efficiently communicated and carried mail to Patna since roads and telegraph lines took time to repair.

Urban Planning and Earthquake-safety

Towns across Bihar and in particular the communication hubs and commercially important towns Muzaffarpur and Darbhanga in the north and Munger on the southern banks of the Ganges, all suffered extensive destruction in the densely populated bazaars. People had died in considerable numbers in these bazaars, mainly under the crumbling brick buildings. The envisioned human suffering in future earthquakes motivated new town plans for these crowded urban areas. As a result, reconstruction and town planning approached earthquake safety mainly through the planning of wider roads and more sparsely populated settlements. These plans, however, did not follow a disaster management plan modelled on earthquake safety but on sanitation engineering. The same planning was arguably beneficial for both: lower population density and wider roads between houses improved hygiene conditions while it also served as an argument for risk reduction in future earthquakes. Less congested spaces with wider lanes would improve the chances of escaping the falling bricks. Building wider roads was also popular with businessmen as it would facilitate trade, although the planning and modernisation through, for instance, electrification attracted criticism for costs it entailed for the residents. This modernisation in the reconstruction phase was, therefore both resisted and welcomed by various groups.

In villages of north Bihar, a sub-district officer noticed how houses of bamboo thatch and reeds “naturally rode out the earthquake without any damage as their materials were both light and resilient.” Even though, these materials were suitable in villages with space between the houses, the experience of massive fires had shown how such constructions posed major hazards in the often-congested temporary urban colonies. Mud walls, bricks, tiles and corrugated iron in townhouses controlled the spread of fires, while bamboo and thatched constructions aggravated the fire problem. Even though the dangers of fire in the temporary huts made of grass were well known, they remained the most common type of construction in the reconstruction phase. The frequency of fires in the temporary grass huts was one probable reason for people’s reluctance to move into the organised relief colonies.

Disaster risk reduction during the colonial period undoubtedly still plays a role in today’s society due to its enduring impact on infrastructure and urban planning. Knowing how risk is conceived in a local context helps us to understand how choices are made to deal with a range of hazards. Availability and affordability of construction materials, in combination with reconstruction after disastrous experiences, can have a significant impact on the negotiation of risk in the future. In many ways, policy decisions of today could benefit from taking into consideration how past practices continue to have an impact.

Photo captions: (1) Brick production in the aftermath of the 1934 Bihar-Nepal Earthquake. (2) Brick kiln set up in the aftermath of the 1934 Bihar-Nepal Earthquake. Source: “SCIIA – Service Civil International – International Archives, Bibliothèque de la ville, La Chaux-de-Fonds (Switzerland)”.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this piece are those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of AIDMI.