By Emmanuel Raju, University of Copenhagen, Denmark; Mihir R. Bhatt, All India Disaster Mitigation Institute, India; and JC Gaillard, University of Auckland, New Zealand

While disasters continue to affect millions of people, push many of them into vicious cycles of poverty, processes of risk and vulnerability continue to be created. And recently, with an accelerated pace. This special issue is an attempt to highlight some of the untold stories from a South Asian perspective. These stories and processes of local actions are rarely studied and responded to using different lenses from the region. In this issue, we bring together various themes of caste, gender, the colonial roots of today’s disaster problems and the question of self-rule in disaster governance. And we bring it from many points of view, where some viewpoints so far are untouched.

2024 marks 20 years of the Indian Ocean Tsunami of 2004, which affected millions of people across the oceans. Have the 20 years of learning from disaster responses and recoveries led to less risk creation? Or has the Nepal earthquake of 2015 and the many floods in Pakistan helped to change the landscape of understanding vulnerability and ensuring better disaster governance? All these questions force us to put the processes of vulnerabilisation and risk creation in South Asia, to start with, at the heart of understanding disasters.

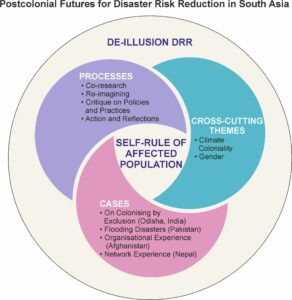

South Asia is ripe for both, postcolonial and de-illusion DRR. Ripe because of a range of reflections as well as concrete results on the ground. As the write-ups in this issue suggest, there are cross-cutting themes on climate, coloniality and gender. There are de-illusion DRR processes calling for co-research, re-imagining, critiquing, and reflecting. There are cross studies on exclusion in Odisha, on flooding in Pakistan, organising in Nepal, and networking in Nepal. All, in the end, point to the greater agency of the affected population: self-rule.

As the diagram suggests self-rule by local people, of all age, gender identities, caste and physical ability, is at the centre of any postcolonial future of DRR. This publication offers three perspectives through which this happens.

The first is through the process of retrofitting self-rule. Making self-rule central is a process through which local people co-research re-imagine, critique policies, and reflect on practice.

Second, we offer four case studies that serve as examples of the process of retrofitting self-rue, its challenges and opportunities. These case studies are from Odisha (India), Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nepal.

Third, we have compiled articles that address cross-cutting issues such as climate change, coloniality and gender. It is our contention that considering these issues is essential for putting self-rule at the centre of de-illusion DRR.

The postcolonial lens provides a powerful framework to support our agenda. By postcolonial we refer to a field of scholarship and praxis that is open to the future, that is, it goes beyond only pushing back against the past and its colonial heritage. Our postcolonial agenda recognises the devastating impact and enduring legacy of colonialism; one where disasters, in the name of humanitarianism and greater good, a powerful illusion in the Nietzschean sense, have been used to hide the imperialist agenda of the West. And imperialism has found new and many dresses to wear to suit the context and the company.

Nonetheless, our agenda acknowledges that terms such as disaster and its cognate concepts as well as the methodologies of assessment and frameworks of policy and practice are (unfortunately) here to stay with us for some time given the normative and powerful worldwide dispositif in place to reduce disaster risk. It is a collective duty to continue to challenge such global and neoliberal injunctions that aim at standardising our understanding of what we call disaster after Western epistemologies and ontologies. This should be a long-term and very goal for all of us in our practice of disaster scholarship as well as in our actions to reduce harm and suffering. A small act of relief does not take much long to turn into a top-down, outside-in, structure.

In this special issue, our goal is less ambitious, yet similarly essential. It is to explore how the colonial legacy, that is, scholarship on disasters as well as policies and actions to reduce risk, is reinterpreted and subverted by local people across South Asia; how, oftentimes, the colonial legacy co-exists with a hidden and subversive set of indigenous practices geared towards understanding and dealing with environmental phenomena, not necessarily seen as hazardous. In this sense, the concept of disaster and associated policies and actions to reduce risk are also an illusion in that the imperialist agenda was doomed to fail because it has always neglected the organic power of local people to be agent of their own life.

This is why our agenda embraces hybridity as a critical lens to understand what we usually call disaster. We acknowledge that the seemingly successful colonial legacy co-exists alongside, rather than fuse with, subversive and lasting indigenous practices. Hybridity thus allows us to look forward and hence not to fall into a nativist or essentialist trap that would both romanticise the past and prevent us from capturing the complexity and reality of a quickly changing contemporary world. However, we have seen that hybridity is neither a marker of subjection to the colonial heritage. It is a sign of resistance, a sign of protest, one that fosters agency and self-rule, one that opens up space for de-illusion disaster.

We hope you will join us in the journey of charting new pathways to unpack disaster risk creation and disaster risk reduction more critically.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this piece are those of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of AIDMI.